Generally, companies don’t like to give promotions. They are expensive and risky. The company has to spend extra money to put a known entity into an unknown situation. There is a risk of failure that didn’t exist before.

This is a sweeping generalisation, but it’s a useful one. You probably deserve a promotion, but on its own, that’s rarely enough to actually get you promoted. There are forces working against you: the cold, hard unit economics of your business. The risk aversion and politics of your managers. Inertia.

In the past decade I’ve worked in roles from entry-level writer to CMO. There were times when I did great work and completely failed to earn promotions. I would point to my myriad successes, talk about my desire for more responsibility and new challenges, and I’d be met with a shrug: you’re doing a great job, but we just can’t do it right now.

On other occasions, promotions would all but fall into my lap. The difference was rarely my effort level, or my persuasiveness—it was my leverage.

Leverage is your ability to instill a need for your company to promote you, a chance for the company to avoid something painful, or gain something wonderful.

From my experience, there are four types of leverage you can use to catalyze a promotion:

The obvious form of leverage is a competing job offer. You are making a bet that your company would rather pay more money than lose you.

This is the “go nuclear” option. It can work, but in my opinion, it’s the least appealing. It requires tons of effort to interview and secure an offer alongside your job. There’s an existential risk: in the worst case scenario, you end up without a job. Even if it works and you earn a promotion, there’s a chance of souring your relationship with your colleagues.

I’ve been in this situation before, and it wasn’t particularly fun, but it worked. This was partly because I worked for an awesome company, and partly because I tried to be…

- Sincere. Resignation can’t be a cynical negotiation tactic—you need to be completely and sincerely prepared to leave your current company, should the negotiation fall through.

- Direct. The more concrete you can be about your reasons for leaving, the changes that would make you stay, and the timeline for the whole process, the easier it is for your current company to respond in a useful way. Avoid vagaries and empty threats of resignation.

- Honest. Be clear about your reasons for leaving, and honest about what would excite you to stay. (And there should be reasons to stay: why try and get promoted at a company you don’t like?)

- Kind. It’s easy for bad vibes to appear during this process, but at the end of the day, this is a business transaction. You can—and should—be amicable through even the messiest departures.

Another form of leverage: building a narrative of promotion. Cultivating some big, public success creates an implicit pressure for the company to reward it.

Promotions need to be socialized throughout your company. It’s easier to get promoted if everyone expects you to be promoted; it creates less resentment among peers, and makes it easier to get budget and justify the expense to company leadership.

There are many talented, hard-working people who are hard to promote because their success is too quiet, or behind the scenes, or humble. They lack a narrative of promotion: it would seem unexpected or unreasonable to promote them, because so few people see their value. It’s much easier to earn promotions when you can point to big, obvious, high-value successes to your name, as well as the steady, compounding wins.

Or put another way: you need to be high efficacy (good at your job), but also high performance (good at demonstrating your success in obvious ways):

Part of this is working on highly-visible projects. Whilst it’s not always possible to conjure career-making moonshots from the ether, it is possible to shift more of your energy towards activities with greater visibility and greater potential upside. Applying to speak at a conference is likely to have a bigger upside than delivering another solid blog post.

You can raise your hand to work on flagship accounts. You can suggest and lead experimental service offerings. You can pilot new roles and responsibilities, build new workflows, pitch talks at big conferences, test out new marketing channels.

Another part of this is vouching for yourself. The more public examples of your success, the easier it is to justify your promotion (and inversely, the greater the collective cognitive dissonance caused by not promoting you).

This can feel incredibly difficult. Most people find it hard to talk positively about their accomplishments. The idea of posting a win in a company Slack channel can reduce the best marketers to nausea.

I’ve always found it helpful to reframe the idea. When you tell your manager what’s going well, you make it easier for them to do their job. When you tell your colleagues about an experiment that paid off or a campaign that succeeded, you’re helping them get better at their jobs, providing a few more data points to illustrate what “good marketing” looks like in your industry. When you celebrate someone else’s success, you make it easier to celebrate your own in turn.

Another type of leverage: developing some form of unique skillset that can’t be easily replaced by someone else.

Some people are obvious “10x employees”, capable of superhuman feats and able to command virtually any salary or promotion they want. But for mere mortals like us, I’ve seen people develop leverage by becoming:

- The face of the company. Employees can become the public face of a company, often by being the most active content creators. Public perception of the company becomes synonymous with public perception of the employee—the company has an incentive to keep them around (and happy). But be wary of taking this too far, and building a personal brand at the expense of your company.

- The mediator between different worlds. When I worked at a content agency, the skilled writer who could also code was one of the most valuable people, because they could translate between the different languages of writing and software development. They could talk persuasively to technical founders, use data analysis to create research reports, and build software prototypes to make our content workflows faster.

- The custodian of mysterious and important company processes. If a company is built on Airtable bases, mountains of Zaps, and tons of integrations, then the person with the API keys is king.

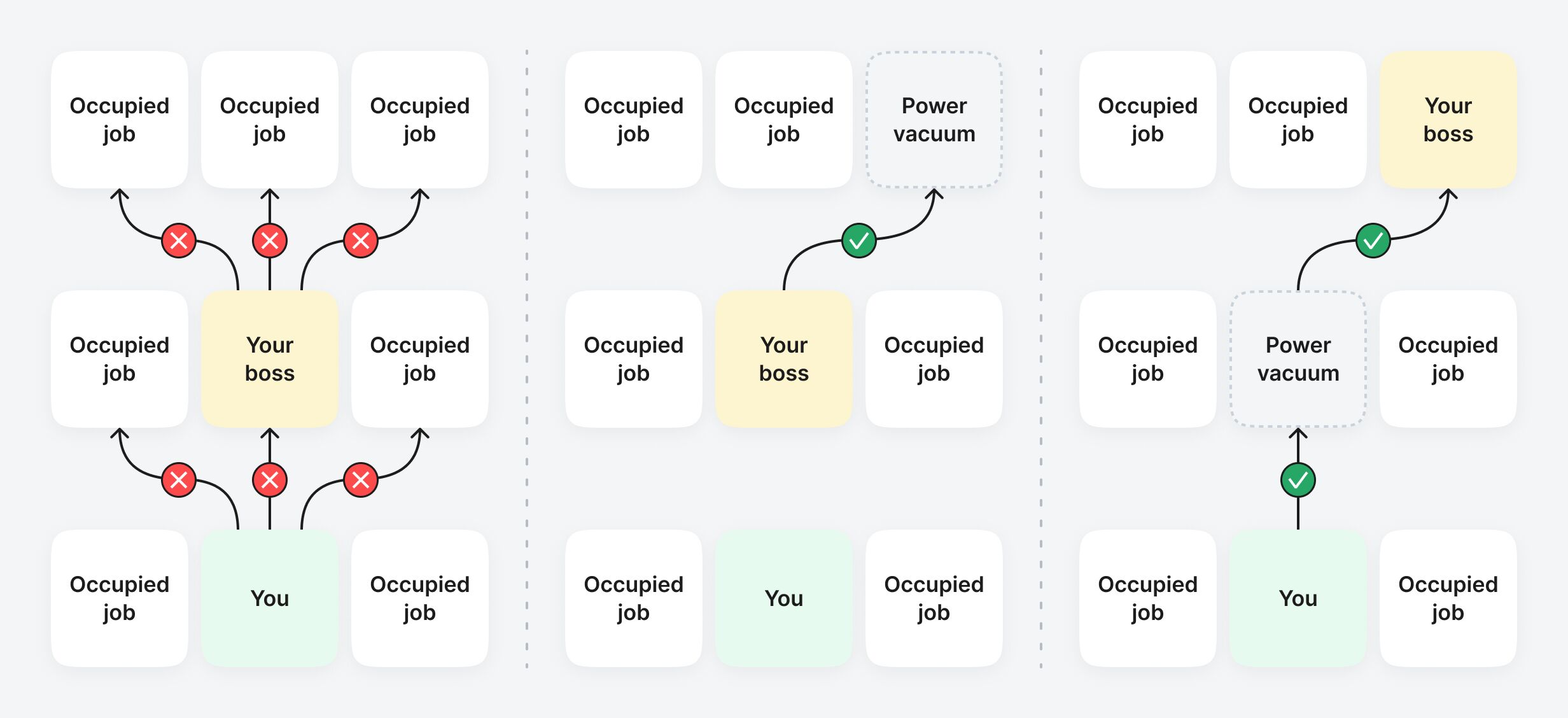

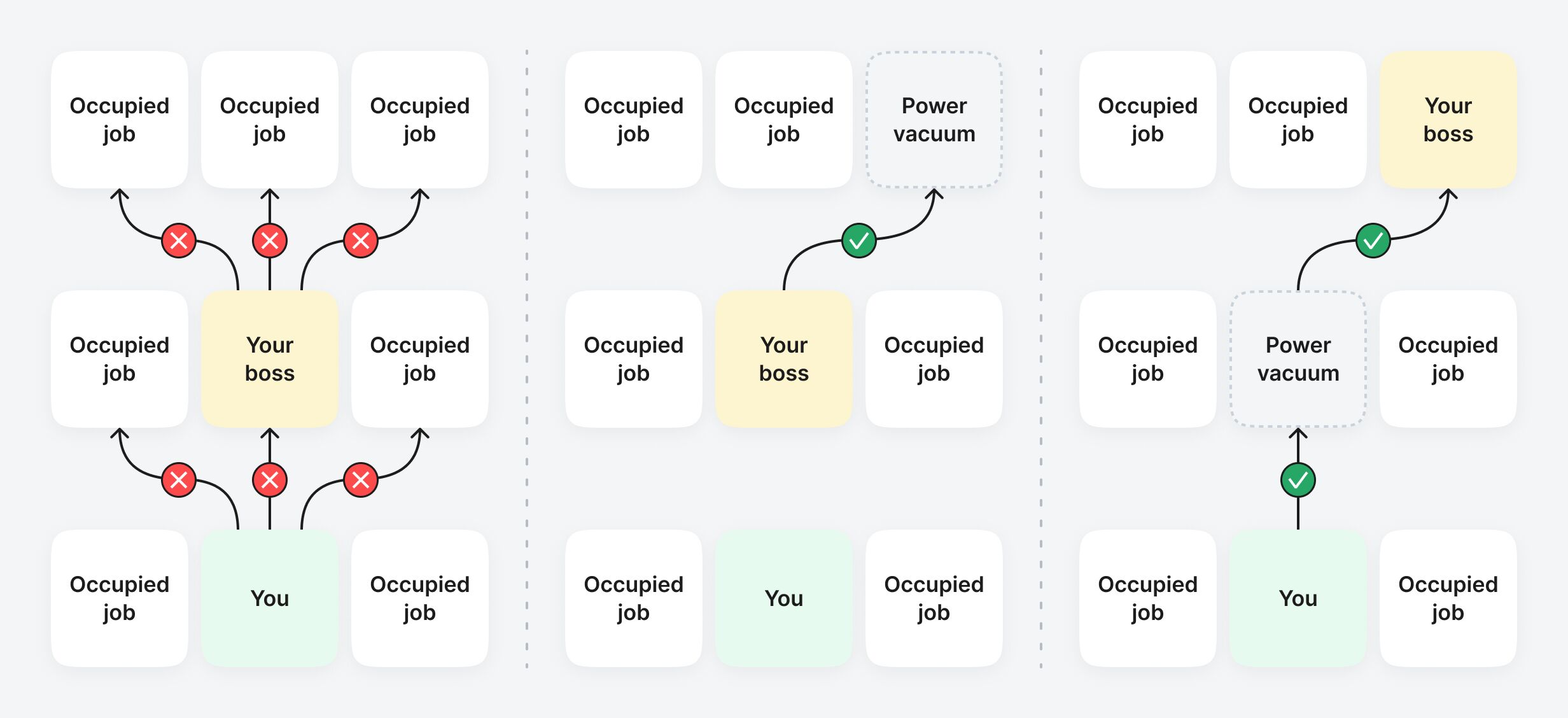

Another type of leverage: allowing somebody else to profit from your promotion. If your upward move also enables someone else to earn a promotion, you can double the potential gain (or risk) to the company posed by your promotion.

I used to imagine promotion as a hand-over-hand vertical climb through the ranks of an organisation. My actual experience has been the opposite: most of my promotions came as a result of slipping into the “power vacuum” created by my manager moving into more senior roles.

This is the reality of promotion at many organizations. For you to move up, somebody above you needs to move up (or move on) to create the space. By supporting their ambitions, you increase the likelihood of a new opportunity opening up, but also create the goodwill and trust needed to position yourself as a suitable successor.

You provide a solution to the problem posed by finding your manager’s replacement. You create leverage by doubling the number of people who directly (and financially) benefit from your promotion.

You can encourage this by working closely with people who you think will do great things. Hitch your wagon to theirs, learn from them, and position yourself as their natural successor.

I love the story my boss at a previous company, Devin, shared with me: when asked what she wanted from her career by her then-CEO, she said “I want your job.” When he moved on to building a new business, she moved into the vacuum and became CEO.

Some companies simply lack the infrastructure necessary for promotion. They aren’t growing. There’s a hiring freeze. The marketing team has lost half its budget. The new CMO doesn’t care about your role.

No amount of Herculean effort will be enough to overcome these hurdles—you’re trying to will into existence something that isn’t physically possible given the constraints of the business.

This is not a moral judgment or a critique: it’s a fact of reality. Getting promoted is not equally viable in every company at every moment of time. There can be a great benefit to staying with companies through these difficult periods, but if earning a promotion is your primary goal, sometimes, you’ll have an easier time doing it somewhere else.